Artemis Cuts: An Analysis for Europe

NASA’s Cuts Represent Both a Threat and an Opportunity for Europe’s Space Ambitions

The Political Pull on the President’s Budget Request

On May 2, 2025, the White House released the “skinny” President Budget Request for Fiscal Year 2026. The President’s Budget Request (PBR) is the annual proposal submitted to Congress for the upcoming fiscal year. A “skinny” PBR is a stripped-down version of the full request, expected later in May. Presidential budgets are essentially wish lists—Congress ultimately decides federal spending.

NASA has seen this before—most dramatically in 2010, when President Barack Obama cancelled the Constellation program. That initiative, a precursor to Artemis, aimed to return American astronauts to the Moon by 2015. The move effectively scrapped both Orion and the SLS (then still in its embryonic “Ares V” form). But legislators from space-faring states—Texas, Florida, and California—pushed back, restoring funding to protect thousands of local jobs.

It is very unlikely that Congress will fully agree with President Trump’s proposal. Capitol Hill remains driven by the representatives’ instinct for political self-preservation. Many Republican and Democratic lawmakers represent districts with significant industrial ties to Artemis. For instance, the SLS program's industrial base spans all 50 U.S. states. Alabama hosts the Marshall Space Flight Center, where Boeing is developing the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS), employing thousands. Florida houses the Mission Control Center and launch facilities. Louisiana’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans manufactures the SLS core stage. Mississippi handles RS-25 engine testing; Texas supports space operations; California builds RS-25 engines; and Utah is home to Northrop Grumman’s solid rocket booster production.

The Gateway cancellation would not only impact European—and particularly Italian—space contractors but also undermine Europe’s political standing and scientific role in future lunar exploration.

Given this vast geographic spread—supporting more than 3,800 employers—the discussion around cancelling SLS will likely be the main friction point in the FY2026 NASA budget debate. Because while NASA reports to Congress, Congress ultimately reports to voters.

Formally, both NASA and Congress will also submit their own proposals—just as the White House has done. The challenge will be finding a “best compromise” among all parties, as the skinny PBR reflects a continuation of strategic ideas previously articulated by both the Trump administration and Jared Isaacman, NASA’s nominated administrator. At its core, the proposal signals intent: cut all programs not deemed essential for establishing a permanent lunar presence—and for beating China to the Moon.

A clearer picture of the Congressional stance on the FY2026 NASA budget is expected to emerge during the summer, since the involved parties will have to reach a compromise before September 30, when the new fiscal year begins. If no agreement is reached by then, the government will have a “green light” to implement its proposal. The negotiations ahead will be tough, but as always, Capitol Hill will have the final word.

What’s In It?

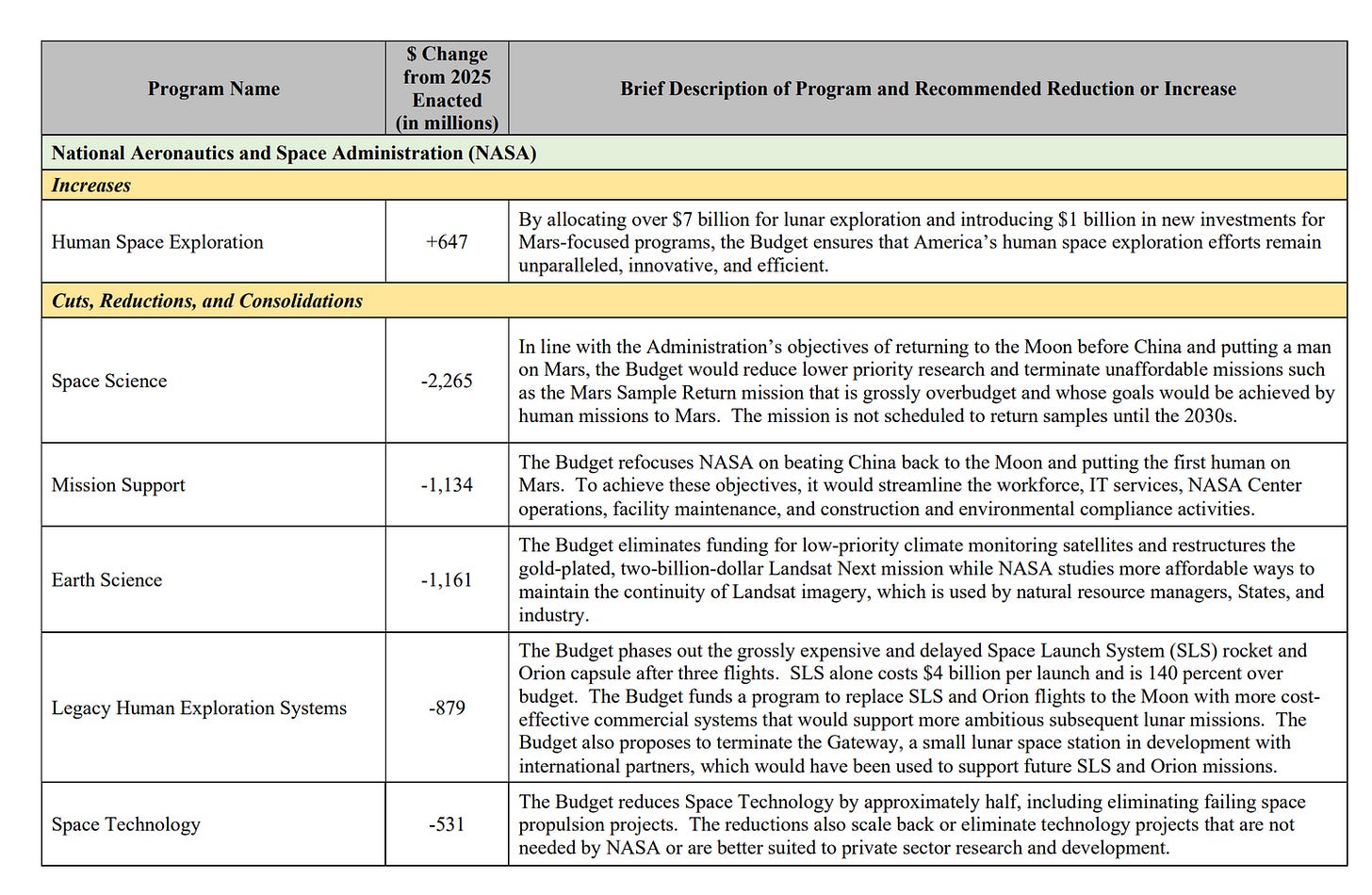

The Trump administration’s FY2026 “skinny” PBR requests a 24% budget cut for NASA—from $24.8 billion in FY2025 to $18.8 billion in FY2026—its lowest funding level since 2015. Specifically, this includes:

$2.265 billion in cuts to NASA’s Space Science programs (a 44% reduction from FY2025)

$1.161 billion in cuts to Earth Science (a 53% reduction)

These figures align with internal memos reported by Ars Technica, which indicated nearly 50% reductions across NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD).

NASA’s public reaction was bizarrely enthusiastic. “President Trump’s FY26 Budget Revitalizes Human Space Exploration,” read the press release. Acting Administrator Janet Petro added:“This proposal includes investments to simultaneously pursue exploration of the Moon and Mars while still prioritizing critical science and technology research. I appreciate the President’s continued support for NASA’s mission.”

Still, while it’s true that the cuts aim to focus NASA on lunar and Martian missions, the increases for human spaceflight are modest: about an 8% bump, with a $647 million increase on top of the $7.6 billion in FY2025. Moreover, the current space strategy is a far cry from the Apollo era. In 1966, NASA received $5.93 billion—about $58.5 billion in today’s dollars—three times the proposed FY2026 budget. Isaacman’s gamble is to “achieve the impossible” on a third of Apollo’s budget. Can he?

When it comes to Moon and Mars exploration missions, the PBR highlights several key cuts that will inevitably affect the European space sector and ESA’s agenda, especially in relation to Artemis and beyond. Here are the main programs and missions at risk—should these cuts be confirmed—that will also impact Europe:

Under the FY2026 “skinny” PBR, NASA’s Science Mission Directorate faces a 44% reduction that would eliminate the Mars Sample Return mission, while a separate $879 million cut to Legacy Human Exploration Systems targets three of Artemis’s cornerstone programs: the Space Launch System (SLS), the Orion crew capsule, and the lunar Gateway station.

Key Missions Facing Cuts

SLS, Orion, and Gateway Costs for the U.S.A.

According to The Planetary Society, from 2011 to Artemis I’s 2022 launch, NASA spent:

$23.8 billion on the SLS

$20.4 billion on Orion (since 2006)

$ 5.7 billion on Exploration Ground Systems

That’s $49.9 billion invested in core Artemis infrastructure. The SLS has always been the most criticized element of Artemis. Under the Trump administration, criticism intensified—most notably from SpaceX, whose Starship system represents a competitor despite its unproven reliability. Critics point to the SLS’s high cost per launch (approximately $4 billion, including ground and launch support) and its non-reusable design. Yet while NASA admitted in 2022 that SLS development exceeded budget by 42.5%, it has flown. Starship, by contrast, has not yet demonstrated the several critical milestones, including the in-orbit refueling of cryogenic propellant multiple times.

As Dan Dumbacher, adjunct professor at Purdue University, noted during a recent Space and Aeronautics Subcommittee hearing: “NASA's current plan to return people to the Moon requires approximately 35 to 40 Starship launches to first demonstrate the capability on an uncrewed mission, and then execute the first human mission planned for Artemis III. I ask this: can 40 launches, development and demonstration of the undeveloped and undemonstrated in-orbit rocket fuel station, and integration of a complex operational scenario across multiple systems, all successfully occur by 2030? The probability of success for this plan is remote at best”

The SLS remains the only government-operated rocket to complete a lunar mission, delivering the Orion spacecraft into lunar transfer orbit during Artemis-I. (Note: Discussing the needs, political significance, compromises, and costs associated with the SLS is beyond the scope of this article. However, for those interested, see Casey Dreier's analysis for The Planetary Society)

Because it is largely built outside the United States and is not strictly necessary for a crewed lunar landing, Gateway is especially vulnerable to cuts under the Trump administration.

When it comes to Orion, the debate continues. Saved from cancellation after Obama’s 2010 cuts and repurposed for deep-space crew transport, Orion today is NASA’s only capsule rated for lunar missions. (China may field its own deep-space capsule—Mengzhou or “Dreamboat”—if tests succeed.) That said, Orion faces critical issues flagged in the Office of Inspector General’s audit of Artemis I, including problems with its heat shield (Thermal Protection System), separation bolts, power distribution, and intermittent communications. These anomalies pose serious risks to crew safety and must be resolved before Artemis II. Still, developing a new, cheaper capsule would require fresh investment and time—raising the question of whether rebuilding from scratch makes sense.

SLS and Orion are theoretically independent: cancelling one need not doom the other. Yet significant structural, aerothermal, and abort-system modifications would be required to pair Orion with an alternative launcher. Strategically, they function almost as a single system. If Congress cuts SLS, is it worth saving Orion? And vice versa. That interdependence likely explains why Orion sits on the cancellation list alongside SLS, but new capsule may be as costly and time-consuming as reworking the existing one.

Gateway—Artemis IV was to debut the lunar-orbiting Gateway station, with launch of its core modules by December 2027 at $5.3 billion. That launch would have delivered the first Gateway components—the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE), awarded to Maxar Space Systems, and the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO), awarded to Northrop Grumman—while SpaceX handled the logistics vehicle. Four additional elements were then to be added during Artemis IV, V and VI to complete the station’s sustained configuration. Those elements included ESA’s I-Hab, Lunar View and Lunar Link; the Canadian Space Agency’s robotic arm, the UAE’s airlock, and JAXA’s life support systems and critical component of the I-Hab and HALO modules. But the skinny PBR proposes terminating SLS and Orion after Artemis III—and cancelling the Gateway entirely, before construction begins.

Mars Sample Return

Mars Sample Return (MSR)—a flagship planetary science mission—is also on the chopping block. The PBR characterizes it as “an unaffordable mission… grossly over budget and redundant with future human Mars missions.” Perseverance has cached dozens of rock samples; MSR would retrieve them via a future rover and Earth-return orbiter. But cost overruns led to its suspension in 2024, as then-administrator Bill Nelson confirmed.

ESA was a major partner, developing the Earth Return Orbiter (ERO)—which would rendezvous with a sample capsule in Martian orbit and carry it home, marking ESA’s first interplanetary round-trip and the largest spacecraft ever at Mars. Despite design maturity, ERO is now on hold. ESA retains the option to adapt ERO to any new NASA plan—but for now, cancellation seems likely.

The Consequences for Europe

ESA has deep stakes in these programs:

European Service Module (ESM) for Orion

I-Hab, Lunar View, and Lunar Link for Gateway (under a 2020 MoU)

Earth Return Orbiter (ERO) for MSR

Financially, the impact is substantial.

In 2014, ESA awarded Airbus Defence and Space a €390 million fixed-price contract for Orion’s ESM.

In 2021, Airbus won a €650 million contract to build three more ESMs.

In 2020, Airbus secured €491 million for ERO.

ESA has also committed funding for Gateway’s Lunar I-Hab, Lunar View, and Lunar Link modules.

The European industrial consortium for Orion under ESA’s umbrella centers on two main sites: Airbus Defence and Space in Bremen, Germany—ESA’s prime contractor for the European Service Module (ESM), which literally sustains the Orion capsule for its journey to and from the Moon—and Thales Alenia Space in Turin, Italy, which as a subcontractor provides the primary and secondary structure, including several critical systems for the ESM. Cancelling the Orion program would be a severe blow to Germany’s space industry and economy; the Italian sector would also suffer, though to a lesser extent.

While SLS and Orion may find champions on Capitol Hill—thanks to the jobs and political capital they represent—the Gateway faces a different fate. In the U.S., Gateway was conceived as a “tailored program” to keep international partners from pursuing rival initiatives (for example, China’s IRLS). Yet because it is largely built outside the United States and is not strictly necessary for a crewed lunar landing, Gateway is especially vulnerable to cuts under the Trump administration.

From a European standpoint, the reverse is true: Gateway is the principal concern. Manufactured heavily in Europe—translating into multi-million-dollar contracts for European industry, especially in Italy—it embodies Europe’s scientific and strategic commitment to Artemis. Its cancellation would not only impact European—and particularly Italian—space contractors but also undermine Europe’s political standing and scientific role in future lunar exploration.

ESA’s Diplomatic Response

On 5 May 2025, European Space Agency - ESA issued a formal response to the PBR. The tone was measured. The agency deferred any decisions to its June Council meeting, where Member States will assess options and consider contingency plans. A Ministerial-level Council will follow later in the year in Bremen.

Director General Josef Aschbacher reiterated ESA’s commitment to international collaboration: “ESA and NASA have a long history of successful partnership, particularly in exploration – a highly visible example of international cooperation – where we have many joint activities forging decades of strong bonds between American and European colleagues.”

The diplomatic tone was expected. ESA is not a political actor. It does not have the mandate to challenge national strategies. It's also important to remember that NASA and ESA will still be here four years from now, and it's unwise to burn bridges unless absolutely necessary—and even then, diplomacy and quiet firmness tend to prevail. And yes—when NASA, the most powerful space agency in the world, calls you to say they’re changing plans, you adapt. You accommodate.

But adaptation is not submission.

ESA must now reassess its priorities, prepare alternative strategies, and deepen ties with other space partners—Canada, Japan, the UAE. There is also an opportunity here: to redefine Europe's space strategy with greater independence, outside the shadow of its big brother. (In this sense the recent signing a new joint statement of intent with India on cooperation “for human space exploration focusing on low Earth orbit, and in a secondary stage on the Moon” goes in that direction).

The question remains: how will Europe play its cards?

Possible Future Scenarios

ESA Takes the Lead - One tempting option is for ESA to assume full political, managerial, financial, and technical responsibility for Gateway—stepping into NASA’s shoes while keeping CSA, JAXA, and UAESA on board. This path would preserve existing hardware and maintain Artemis’s international cohesion, preventing a unilateral U.S. shutdown from fracturing partnerships.

However, a complete ESA takeover is complicated. The U.S. is still in charge of critical Gateway components—Maxar Space Systems for the PPE, and Northrop Grumman for HALO (albeit HALO is produced in Italy). If NASA withdraws, ESA and its partners would need to cover the US Governament Accountability Office’s $5.3 billion estimate for initial Gateway capability (PPE + HALO, launch vehicle, integration, and support)—roughly 30 percent of ESA’s entire 2022 budget, just to launch half of the station.

Moreover, Europe lacks a heavy-lift launcher capable of delivering Gateway modules to lunar orbit. ESA would have to secure funding not only for hardware but also to develop or charter a suitable rocket. That means asking Member States—amid political uncertainty and rising defense pressures—to commit billions annually for at least 15 years, the station’s expected lifetime. Without unprecedented political resolve, a full takeover remains improbable.

Gateway in LEO - A more speculative idea is relocating Gateway from a Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit (NRHO) to Low Earth Orbit (LEO). But Gateway is optimized for NRHO’s near-continuous sunlight (minimizing thermal cycling and propellant for station-keeping). In LEO, 90-minute day/night cycles would subject modules to hundreds of thermal fatigue cycles each day, and the oxygen-rich environment from Earth’s atmosphere would accelerate corrosion.

Habitable volume also drops sharply: Gateway’s ~3 m-diameter modules versus ISS’s ~5 m. Constrained quarters would reduce crew capacity and comfort, making long stays more arduous. Scientifically, a LEO Gateway adds little beyond ISS capabilities—human presence beyond Earth’s magnetic field would remain untested. In short, moving Gateway to LEO would strip it of its primary purpose.

A Multilateral Consortium - A more moderate—and potentially more sustainable—approach is to transform Gateway into a truly international consortium. ESA could share leadership with CSA, JAXA, and UAESA, while NASA retains a reduced role. Pooling budgets, expertise, and launch opportunities would distribute risk and cost while preserve the station’s design.

This model requires robust diplomatic coordination, aligned timelines, and shared governance—but it mirrors the successful ISS precedent. By leveraging each partner’s strengths and avoiding full economic responsibility on any single agency, a multilateral consortium could ensure Gateway’s future even if U.S. funding wanes.

An Opportunity to Build a Robust Framework

Whatever the outcome of FY2026, Europe may find itself with a unique opportunity amid apparent setbacks. Pressed by shifting U.S. priorities, Europe could finally take the time to establish the core engineering and strategic foundations essential for any spacefaring power.

A truly independent European human-spaceflight capability rests on three cornerstones:

A European cargo and crew capsule

A European heavy-lift launcher

A permanent European LEO outpost (akin to the ISS or China’s Tiangong station)

Can Europe seize this moment? We’ll find out at the next ESA Ministerial meeting in November in Bremen.