Europe’s Launcher Moment: How ESA’s Budget Reveals a New Political Order

A closer look at ESA’s Ministerial reveals a power shift hidden in the launcher lines.

Budgets rarely lie, and ESA’s 2025 Ministerial made its macro-political signals clear enough. Germany stood steady, Italy protected its gains, while France and the UK exposed internal fractures—France looking increasingly inward, and the UK emerging as the lone member state to cut its ESA contribution.

But these top-line movements only tell part of the story.

Behind them lie subtler indicators—numbers that hint at shifting alliances, eroding monopolies, and an emerging political geography of space in Europe. And no department exposes these dynamics as sharply as ESA’s Space Transportation System directorate.

Money tells a clearer story than the speeches.

Launchers: Europe’s Political Seismograph

If we want to understand where Europe is heading, we must study the launcher portfolio, where the power play unfolds.

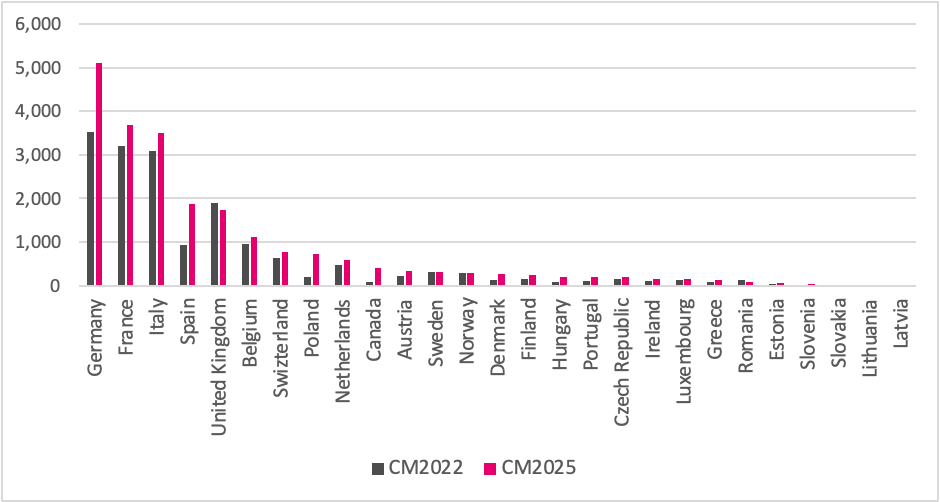

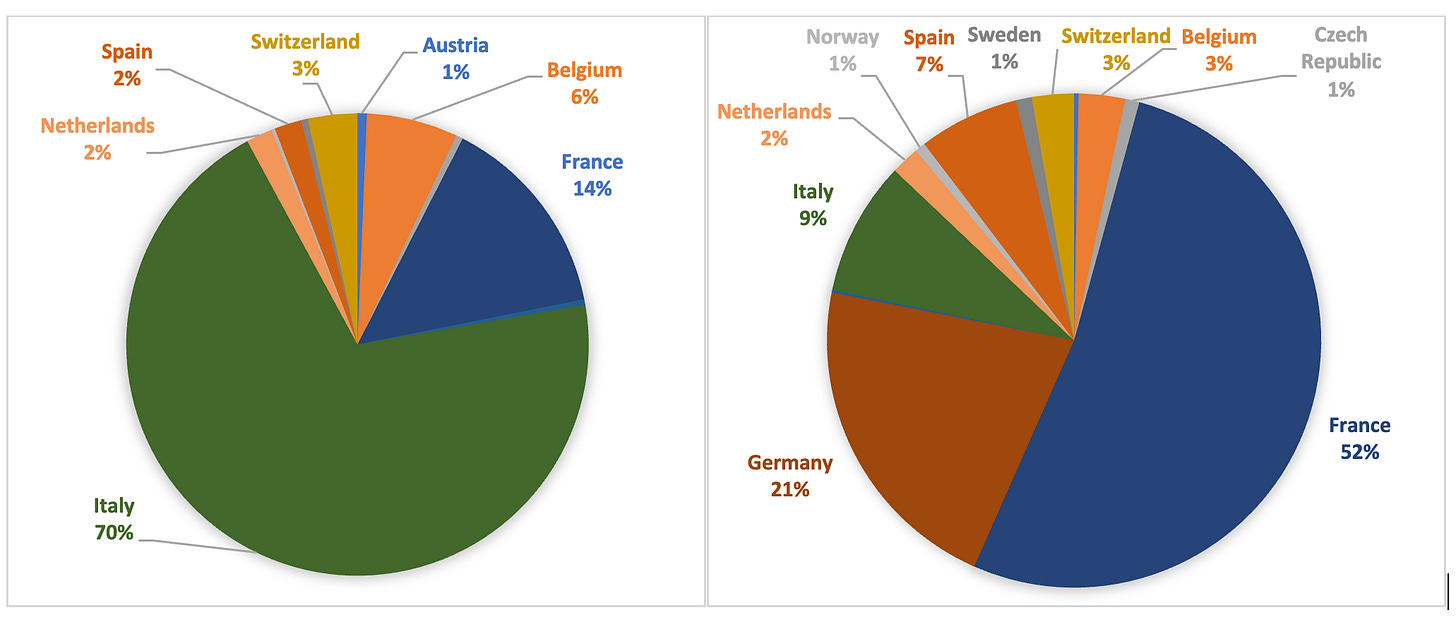

Follow the money and the picture sharpens: France between 2019 and the latest ministerial covered more than half of Ariane-related activities, while Italy financed around 70 percent of Vega-C. For decades, this duopoly suited everyone. ArianeGroup and Avio dominated the market, and the industrial returns aligned neatly with national priorities. There was no alternative, so the political question never arose.

But the market has changed. The centre of gravity has shifted to LEO; commercial customers prefer smaller payloads; and the rise of mega-constellations requires reusability to make launch costs economically sustainable. Heavy, government-oriented rockets like Ariane 6 and Vega-C remain essential—Europe still needs them for institutional missions—but they cannot carry the ambitions of a scalable, commercial “space economy.” Something else is required.

Enter the European Launcher Challenge (ELC).

The European Launcher Challenge: Fragmentation or Renewal?

Created in Seville in 2023, the ELC allows ESA to behave less like a traditional design authority and more like NASA did with SpaceX in its early days: a strategic customer providing funding, not dictating service specifications.

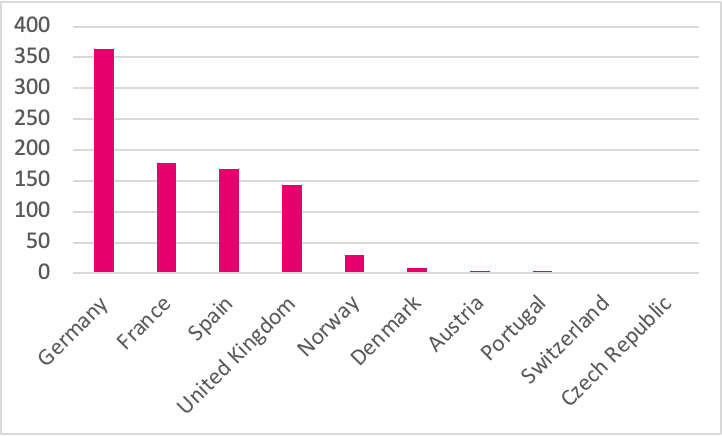

The first cohort—Isar Aerospace (Germany), MaiaSpace (France), Orbex (UK), PLD Space (Spain), and Rocket Factory Augsburg (RFA, Germany)—was selected in mid-2025. Around them, a wider ecosystem is rising: Latitude, HyImpulse, Sirius Space Services. Europe suddenly has more launch startups than launchpads (literally).

Depending on one’s perspective, the ELC is either a waste of resources that slices an already thin envelope into fragments too small for any company to truly break through, or a clever political manoeuvre to dismantle a decades-old monopoly and foster a multi-polar, diversified, commercially competitive European launch market.

France is under pressure. Germany is financing both sides of the chessboard. Italy is behaving as if the ELC does not exist.

These new rockets will not take anything to GTO, nor to the Moon. They are built for feeding the only space economy we can hope for —LEO communications and PNT. Lightweight, high-cadence, cheap access to LEO is the missing link, and the market knows it.

The Ministerial subscription breakdown confirms this shift. Countries that never invested in Ariane or Vega—and never took part in the traditionally closed launcher market—are now placing their bets: Spain poured €169 million into PLD Space, the UK committed €144 million to Orbex, and Norway allocated €29 million to Isar Aerospace, not out of industrial generosity but because Isar is the main customer of the Andøya commercial spaceport. The monopoly is cracking, and countries are beginning to act accordingly.

The Spaceports Story

Launchers are only half of the equation. Spaceports are the other half—and they mirror the same political shift.

Since 1964, Kourou has been the only official European spaceport—despite being located in South America. It is currently financed by the member states for roughly €140 million per year, with additional, larger contributions from France.

But Kourou’s centrality is now being challenged by new contenders: Andøya in Norway, the Azores in Portugal, and SaxaVord and Sutherland in the UK. These are commercial spaceports, openly positioning themselves as complementary—or outright alternatives—to Kourou.

The real question is whether ESA and the member states will support the growth of this competition, or continue to prioritise Kourou alone. It is a dilemma that mirrors the broader trend we see in the Ariane ecosystem.

A Monopolistic System Under Strain: France, Germany and Italy at a Crossroads

While smaller nations push for a geopolitical reorganization of Europe’s launcher landscape, the question becomes: what are the three traditional launcher powers doing? As always, the money tells a clearer story than the speeches.

France is under pressure. For Paris, launchers are not merely an industrial and military asset—they represent decades of investment, workforce stability, sovereign expertise and geopolitical leverage. And although France remains the primary investor in Ariane 6 and continues to lobby for a centralized, vertically integrated launcher monopoly, it is also hedging. MaiaSpace is the obvious indicator, but emerging players like Latitude hint at a broader strategy: keep the heavy architecture alive while quietly cultivating light, alternative launch options. France appears determined to preserve its leadership, but also to avoid being cornered by its own legacy.

Germany is financing both sides of the chessboard—propping up Ariane while simultaneously heavily investing in startups that could one day erode Ariane’s dominance. If this isn’t a source of tension with France, it soon will be. Berlin’s dual-track approach gives it leverage in any future configuration of the European launcher market.

Italy, meanwhile, is doubling down on Vega and behaving as if the ELC ecosystem does not exist. Unlike France—which invests in small launchers through MaiaSpace—Italy has made no comparable move. And this is strategically difficult to justify. Italy has just opened four factories dedicated to lightweight satellite manufacturing but lacks a national launcher suited for low Earth orbit. Vega-C is not a low-LEO, high-cadence rocket. For Europe’s third-largest spacefaring nation, failing to invest in at least one reusable, small-launch option is a gap in strategy. Does the silence at the Ministerial reflect a political instinct to protect Avio, or simply limited budgetary room for Italy to enter the small-launcher segment at this stage?

Taken together, these choices mark a deeper geopolitical shift. Europe is moving away from the familiar triad of France–Germany–Italy, with Brussels as coordinator, and toward a constellation of mid-sized and smaller nations asserting real influence. Spain’s €1.871 billion, Belgium’s €1.117 billion and Poland’s €735 million signal this shift clearly, as do the strategic ambitions behind Portugal’s €205 million and Norway’s €297 million.

And at the centre of this new geometry sits Germany. With the financial weight to tilt the system in whichever direction it chooses, Berlin can resurrect the old order, empower the emerging distributed ecosystem, or—intentionally or not—unleash fragmentation.

ESA’s recent moves—exploring new centres in Norway and Poland and preparing a visit to Portugal—suggest an institution attempting to reflect this changing political geography while still maintaining equilibrium with the traditional heavyweights. Balancing these forces will define the next decade.

And the next years will be interesting.

[1] Vega-C elements include high-thrust engine development, the CM25 Vega-C product-adaptation subelement, CM25 Vega Exploitation Accompaniment, and Vega-C SEATS. Ariane elements include the Ariane 6 product-adaptation element, the CM25 P120C product-adaptation element (a booster shared by Vega-C and Ariane 6), the CM25 Ariane 6 Exploitation Accompaniment, and the Ariane 6 SEATS. The budgets per nation represent the totals published in the 2025 final official ESA document and include contributions made available in 2025 as well as from previous years. They should therefore not be interpreted as funding allocated exclusively for launcher activities in 2025.

The article was edited to correct the annual funding destined from ESA to Kourou spaceport.