Rethinking the Size of the Space Economy

Are satellite-enabled services inflating the industry’s true value?

The GNSS and Satellite TV Economy

Every year, consulting firms, financial groups, and independent entities release assessments of the global space economy. For 2024, these figures range between $400 and $600 billion, with projected annual growth between 3 % (BryceTech) and 7.8 % (The Space Report). In most accounts, satellites are presented as the principal driver of this expansion. BryceTech estimated that $293 billion, 71 % of the sector, derived from satellite-related revenues.

Similarly, The Space Report valued the global space economy at $613 billion in 2024, of which $480 billion came from commercial infrastructure, products and services—roughly 78 % of the total.

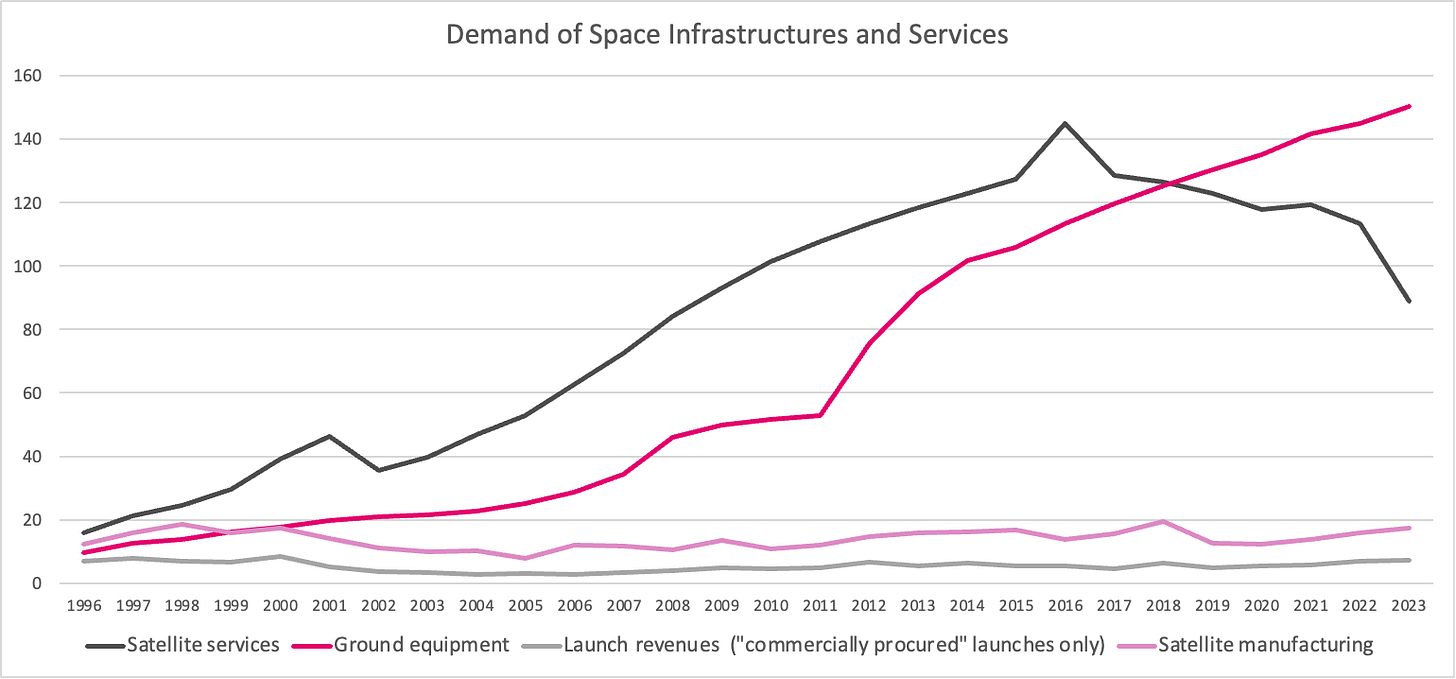

Within the satellite domain, two categories dominate: ground equipment ($155 billion) and satellite services ($108 billion). Yet these categories are themselves highly uneven. In ground equipment, most revenue comes from GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) related equipment - $118.9 billion. In services, the lion’s share comes from consumer services like satellite TV, radio, and broadband ($85.2 billion), and in particular Satellite TV (DBS/DTH) services ($72.4 billion).

According to the European Union Agency for the Space Programme (EUSPA) 2024 EO and GNSS Market Report, smartphones and wearables account for up to 90 % of GNSS device sales, worth about €70 billion in 2024. When apps that rely on GNSS (mobile banking, tourism, gaming, etc.) are included, the total figure of GNSS revenues rises up to €260 billion per year.

Similarly, satellite TV services major revenue comes specifically from sales representing the final step of the Satellite broadband value chain, when consumers buy subscriptions from providers such as DirecTV.

In short, the largest “space economy” revenues do not come from rockets or satellites. They come from chips inside smartphones and satellite-TV subscriptions.

Where Does the Money Go?

Both GNSS devices and satellite broadcasting fall into what is called the consumer-end terminals, or sometimes the reach segment (see for example the terminology used by the World Economic Forum Space Economy Report 2024). These are markets enabled by space infrastructure, but they are not part of the core space systems infrastructure. That infrastructure is generally defined as the hardware backbone: launch vehicles, spacecraft (satellites, probes, capsules, etc.), ground infrastructure such as uplink and downlink stations, launch sites, production and transport facilities, and mission data transmit/receive terminals.

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis defines the space economy broadly, including any goods or services that depend on space inputs. By that measure, counting smartphones, chips and TV subscriptions is legitimate. However the problem is not semantic but practical. One can distinguish between space systems—the core industrial activities—and the broader space economy, the benefits those systems enable. The trouble begins when policymakers, investors, or the public blur the two.

How much of this revenue actually flows back to the satellite manufacturers and launch providers at the core of the industry?

For parts of the sector, this blurring is convenient: it allows to present a booming “space economy” when in fact much of the growth is occurring in the mobile economy or the media sector. The fascination with the word “space” helps make the case of investing in the space business more compelling. But there is a crucial distinction between revenues enabled by space and revenues earned by the space sector itself.

EUSPA’s list of top GNSS companies illustrates the problem. The value chain includes Apple, Samsung, Ford, Google, Facebook, and Microsoft. Hardly firms that belong to the space sector. These companies profit from GNSS-enabled services. But how much of this revenue actually flows back to the satellite manufacturers and launch providers at the core of the industry?

Eurospace data collected through the past decade shows that while ground equipment sales are booming, revenues from launch services and satellite manufacturing remain flat. That suggests there is little evidence that smartphone-driven growth translates into significant gains for the upstream space sector.

Even apparent growth in satellite manufacturing is uneven. BryceTech reported a rise in 2024, but the increase was concentrated in the United States. Outside the U.S., revenues actually fell from $9.3 billion in 2023 to $6.3 billion in 2024. The available data do not specify the cause, but given the scale of SpaceX’s Starlink deployments, it is reasonable to hypothesize that much of the U.S. growth is attributable to that single program.

Commercial Market or Government Market?

Industry reports frequently describe the commercial sector as the engine of growth. But two issues complicate that picture.

First, there is the risk of double counting. When NASA pays Rocket Lab to launch a satellite, the same expenditure can appear twice: once as part of the government budget, and again as Rocket Lab’s commercial revenue. This overlap may give the impression of a larger, more diversified market than actually exists. It also difficult to understand how these revenues were calculated for the lack of methodology.

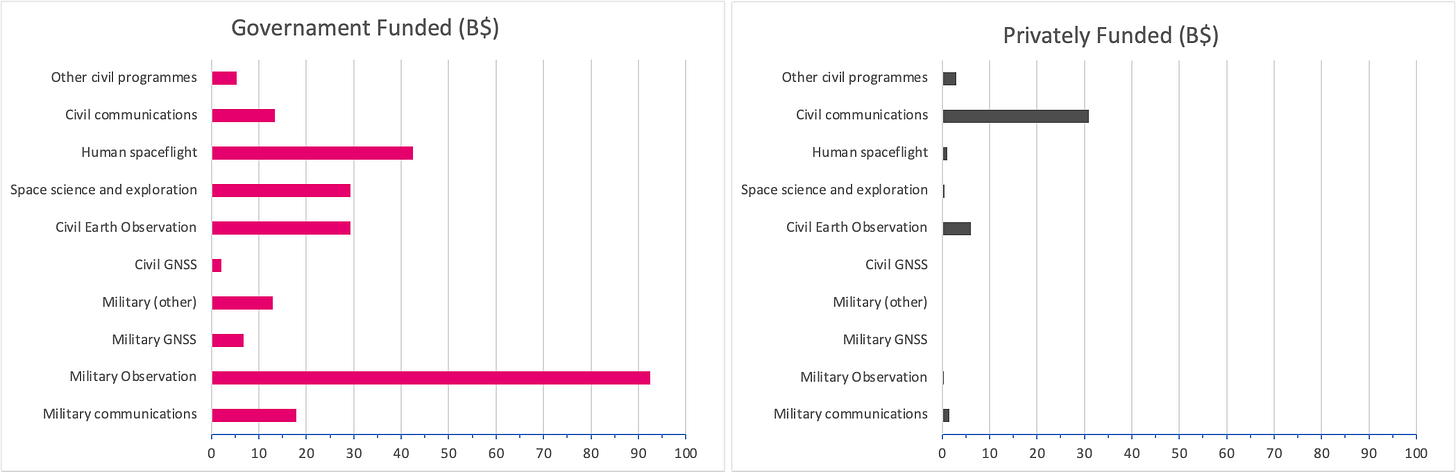

Second, there is the question of who the customer really is. In many cases, the sole purchaser of those commercial services is the government itself. For example, BryceTech notes that 82 % of U.S. satellite manufacturing revenues in 2024 come from government contracts. That distinction matters: a commercially procured service, paid for by government funds, is not the same as a commercially financed market in which private buyers drive demand. In fact, data show that between 2020 and 2024, governments worldwide financed $252 billion in space infrastructure. Private entities contributed just $48 billion, two-thirds of it in telecommunications.

Starlink remains the notable exception: a private company selling services directly to consumers. Yet it is an outlier, not the rule. Without Starlink, the industry remains overwhelmingly dependent on public funding.

The result is a sector where private companies provide services, but governments remain the primary customer. This distinction between commercially procured and commercially financed is often blurred in reports, giving the impression of a self-sustaining private market that does not yet exist.

Why Inflated Numbers Matter

Painting the space economy as a booming private market has consequences. It can encourage investors to pour money into ventures that appear promising on paper but remain structurally dependent on government spending. Reports that emphasize consumer-driven revenues risk presenting a trillion-dollar future that belongs more to telecoms than to aerospace.

For investors, the true opportunities today may lie not in rockets or satellites but in applications and devices that integrate space-based services into consumer products. For space companies, the lesson may be to follow SpaceX’s model with Starlink—controlling the value chain from manufacturing to end-user sales, and build a mobile app you can charge for.

A narrative of expansion

The global space economy is substantial, and its contributions to other industries are undeniable. But the headline figures, $400 billion, $500 billion, even $600 billion, should be treated with caution. They reflect the economic impact of space technologies on consumer markets, not the financial health of the space sector itself.

The winners today are companies like Apple, Samsung, Google, and Facebook, firms that rely on space signals but operate outside the traditional space industry. Meanwhile, the backbone of the industry, launch providers, satellite manufacturers, and space agencies, remains reliant on public budgets.

Reports that blur this line are certainly useful for arguing the sector’s relevance to governments, but they risk misleading investors and obscuring the very real need for continued public support. Without transparency, the conversation shifts from how to strengthen the upstream industry to a narrative of expansion that rests more on perception than on reality.

All data from Bryce Tech/Satellite Industry Association, unless specified.

This is a solid analysis and something I've long suspected as well. The space industry is trying to paint a picture of a booming commercial economy that simply does not exist, and won't for quite awhile. When I started working with [redacted company], they were adamant that they didn't want to be just another government subcontractor like every other space company at the time. By the time I left, their largest customers were the NRO and NASA and they've solidly pivoted toward defense. Outside of navigation and telecom as you've outlined in this article, we haven't yet proven enough commercial use cases to make a truly thriving ecosystem of commercially viable companies.

So good to see the numbers broken down into reality